Over the years, we have heard much consternation from our clients regarding a plaintiff strategy called the “Reptile Approach.” We have seen this approach become more and more popular—not to mention effective—during depositions and trial among plaintiff attorneys. This article provides a brief general overview of the Reptile Approach and offers a few simple suggestions for defending against it.

What Is the Reptile Brain Trial Strategy?

In their book, Reptile: The 2009 Manual of the Plaintiff’s Revolution, authors Don C. Keenan and David Ball advocate persuading jurors by appealing to their “reptile brains”—the “oldest” part of the brain and the part responsible for primitive survival instincts. In books, videos, and seminars, Keenan and Ball advise plaintiff attorneys to demonstrate to jurors the immediate danger posed by the actions of defendants because, as they put it, “when the reptile sees a survival danger, even a small one, she protects her genes by impelling the juror to protect herself and the community.”

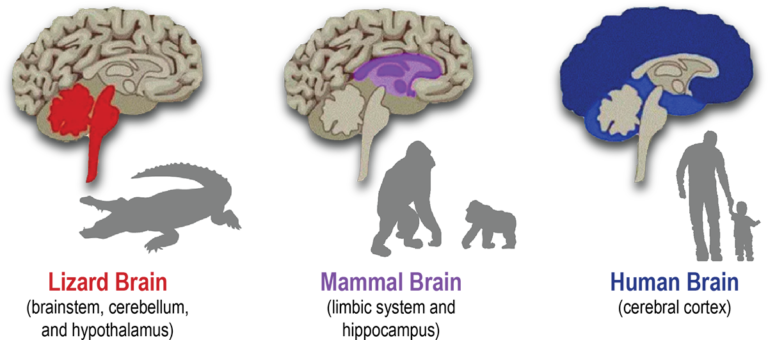

The “reptile approach” advocated by these authors has its roots in an evolutionary theory of human brain development. According to this theory, the human brain consists of three levels of functioning:

1. Reptilian Complex

The reptilian complex is the earliest portion of our brains; it contains aspects (e.g., a brainstem, cerebellum, and hypothalamus) that we share with other animals, including reptiles. Portions of the brain in the reptilian complex govern our most basic life functions (e.g., hunger, breathing) and primitive survival instincts (e.g., fight or flight).

When survival becomes threatened, this part of the brain takes over and can overpower logic and reason.

2. Paleomammalian Complex

The paleomammalian complex, the next most recent development in the human brain, contains aspects (e.g., a limbic system and hippocampus) that we share with other mammals. This complex governs our higher emotions—such as separation distress or playfulness—and grants us the ability to socialize and communicate with one another.

3. Neomammalian Complex

The neomammalian complex, largely comprised of the cerebral cortex, is the most recent addition to the human brain and is believed to govern our logic and higher reasoning functions. This is the area of the brain that allows us to do math and science, and to solve complex problems through reason.

Hallmarks of the Reptile Strategy in Litigation

The plaintiff Reptile Strategy aims to influence jury decision-making by appealing to the reptilian complex of jurors’ brains. That is, plaintiff counsel uses tactics to activate jurors’ survival instincts in hopes that they will make decisions based on instinct (i.e., fear) rather than logic and reasoning.

While there are several tactics that Keenan and Ball recommend, the keystone of their strategy is to focus on danger and community safety:

Establish Danger to Community

One of the most important concepts of the Reptile Approach is the concept of the “Safety Rule.” A safety rule is a universal principle of how people should behave—e.g., a doctor must not needlessly endanger a patient.

A plaintiff attorney who is using the Reptile Approach will point out to jurors a general safety rule, get defense witnesses to agree with the rule, demonstrate to jurors how the defendant broke the safety rule, and suggest that breaking the rule put the entire “community” at risk, thereby “awakening the reptile brain” in the juror. Keenan and Ball illustrate this concept with the phrase “Safety Rule + Danger = Reptile.”

Jury Has the Power to Improve the Community’s Safety

Showing the danger is only the first step. The second step is convincing jurors that they have the power to reduce or eliminate the danger. In fact, another aspect of the Reptile Strategy is convincing jurors that they are the only ones with that power, and that they should exercise that power by finding in favor of the plaintiff and awarding a large amount of monetary damages.

In essence, the Reptile Approach subtly suggests to jurors that they should award compensatory damages to punish the defendant and deter others. Attorneys using this strategy may even suggest that without a “proper” verdict and an “appropriate” punishment, the danger to the community will actually be increased.

The Impact of the Reptile Brain Approach on a Jury

This approach is especially effective in product liability, transportation accidents, medical malpractice, and environmental contamination cases. The sequence begins in depositions and carries over to trial, from voir dire to closing argument.

In his article on the Reptile Approach, David C. Marshall describes some of the deposition questions (i.e., Safety Rules) posed by a plaintiff attorney to a representative for a defendant car manufacturer:

- “Does [the defendant] agree that car manufacturers must make vehicles that are free from defects in materials and workmanship?”

- “So [the defendant] agrees that if a car manufacturer makes a vehicle that has a defect in materials or workmanship, and someone is injured because of that defect, then the car manufacturer is responsible for the harms and losses caused?”

- “Does [the defendant] agree with the statement that car manufacturers must make their vehicles so they operate the way the manufacturer represents they will operate?”

- “And if a vehicle does not operate the way in which it is represented it will operate, and a person is injured, then the car manufacturer is responsible for the harm caused to that person, isn’t it?”

The questions are posed in such a way as to make the witness appear foolish if they do not agree with the premise. This strategy has a way of garnering high settlements—because depositions that should have gone well have instead produced soundbites that reinforce the plaintiff themes.

The questions are also designed to demonstrate to the jury that the defendant broke the safety rule. By showing the rule broken, the theory is that the jurors will feel vulnerable and, in order to reduce that danger risk, they will send a proper message to stop this behavior going forward.

Preparing witnesses who you believe will be subject to the Reptile Approach is essential to avoid providing such damaging testimony.

Countering the Reptile Approach

As a theory of human decision-making and brain development, the Reptile Approach lacks scientific support. However, the strength of the approach lies not in its scientific validity, but in the way that it shifts the focus of the trial from the individual plaintiff to the jurors themselves.

The strategy behind the Reptile Approach appeals to humans’ innate selfishness. To the extent that most jurors implicitly ask themselves, “How does this trial affect me?” the Reptile Approach offers them an answer: the defendant’s behavior affects the juror by threatening their family or community.

There are several ways the defense can counter the Reptile Approach:

Remember We Are Not Reptiles

Even if we accept that the brains of humans evolved in the way the authors contend, the fact remains that human brains did evolve. Our brains have other areas that grant us greater cognitive abilities than our lizard forebears.

The Reptile Strategy deliberately ignores these other parts of our brain: the parts that control our logic and reasoning and make us distinctly human. One of the strategies for countering the Reptile Approach is to invoke the “non-reptilian” areas of jurors’ brains.

Emphasize the Details of a Case

The reptilian brain, as described by Keenan and Ball, is simple, one-tracked and without nuance. It does not deal well with complexity. The simpler the plaintiff can make the case, and the more clearly the defense’s “bad behavior” can be demonstrated, the better for the plaintiff.

However, cases are always more complex than the plaintiff would have the jurors believe. Instead of hiding from the complexity, rationally explain it to jurors within your case story. This is not suggesting that you delve into the weeds of complexity, but rather illustrate the areas in which the plaintiff played fast and loose with the case facts and over-simplified them.

Showing the plaintiff was oversimplifying—and was taking things out of context to do so—means the plaintiff’s own strategy will undermine their credibility with the jury.

Refocus to THIS Plaintiff and THIS Case

One of the hallmarks of the Reptile Approach is to focus on the defendant’s behavior and minimize attention to the plaintiff’s harm.

Gone are the days when plaintiff attorneys would emphasize the injuries, pain, and suffering of their clients; not only were they seeing unsympathetic jurors, but this approach also drew attention to the tenuous connection between a defendant’s “bad behavior” and the plaintiff’s injuries. Now that plaintiffs are focusing on the overall threat of the danger of defendants’ actions, the defense should counter by emphasizing that this trial is only about this plaintiff and whether the defendant caused harm in this case.

Show a Defendant’s Behavior Did Not Violate a “Safety Rule”

As stated, Keenan and Ball advocate showing that a defendant’s behavior violated a “safety rule,” a general norm or standard that most jurors accept.

In order to undermine this approach, the defense should show that safety rules are not absolute and that the proper action depends on multiple factors and considerations. The defense may also show how a different safety rule overrides the alleged broken one, or that the rule was not violated. Depending on the circumstances, the defense could establish that it was reasonable to violate the safety rule in the situation, or that the rule was violated inadvertently rather than intentionally.

Fight Fire with Fire

The Reptile Approach offers the plaintiff attorney an opportunity to make the case about the juror. This strategy is also available to the defense attorney. Helping jurors to identify with the wrongfully accused is a key aspect to defending against the Reptile Approach.

For example, asking jurors to explain in voir dire why it is important that the burden of proof fall on the plaintiff is one way to help jurors step into the shoes of a defendant. You can also subtly remind jurors that if they were on trial, they would want an impartial jury that would listen for proof, not just accusations.

In premises cases, it may help to talk about “property owners” rather than your client specifically, or in malpractice cases, to speak about “reasonable courses of action at work” rather than particular professional standards. Tactics like these keep the focus on jurors and encourage them to identify with the defense—and render a verdict that would prevent frivolous lawsuits against people like them.

Conclusion

Simply put, we are not reptiles; we are human beings capable of using logic and reason to arrive at the right decision. Although several years have passed since Keenan and Ball first introduced their Reptile trial strategy, the practices and tactics they advocate are still used by plaintiff firms across the country.

To successfully defend these cases, it is important to understand the strategy and be able to identify when a plaintiff lawyer is implementing it. When using a trial consultant for witness preparation, voir dire, or other trial services, we suggest making sure that your consultant is well versed in identifying a Reptile plaintiff and is informed about the practices for countering such strategies.

With contributions from John Wilinski. Title illustration by IMS Senior Graphic Designer John Ilg.