Recent news headlines have seen no shortage of shockingly large jury damage awards in personal injury, transportation, and toxic tort cases. Such verdicts make it riskier for corporate defendants to take such cases to trial and leave many defense attorneys and corporate counsel alike wondering what changed—and if the trend will ever end.

In an attempt to find defense solutions, Drs. Jill Leibold and Nick Polavin published introductions to the theory of “safetyism” and how it has changed the landscape for corporate defendants, as jurors’ tolerance for risk has reached new lows and their demands for safety have reached new highs (Leibold, J., Polavin, N., Burrichter, C., Kim, M., & Ozurovich, A. Summer, 2023. “The New Normal: Safety-ism and Conspiracies Are Affecting Juries,” In-House Defense Quarterly, p. 17-21; Leibold & Polavin, “The Rise of Safety-ism Has Entered the Courtroom;” Law360, May 3, 2023).

While productive, the authors’ initial research into jurors’ safety assessments hinted at the possibility of even more psychological variables that make up “safetyism.” These questions prompted further research into factors that could influence verdicts and damages. The goal of this article is to establish the basics of “safetyism,” present these newest findings and put forth a series of defense strategies that seek to address the slew of explosive jury verdicts.

The New Era of Safetyism

Although it may appear that jurors’ outsized safety expectations are something sudden and new, they have likely been creeping into the nation’s psyche for years. Decades ago, the 24-hour news cycle hit cable TV after the Three-Mile-Island crisis, milk cartons highlighted missing children at every breakfast table, and media attention on crime in large cities kept communities on high alert. Far from the latchkey kids of the ‘80s, concerned parents began to raise younger generations with extra protections from—and fearful warnings about—the world’s dangers.

“Safetyism,” coined by authors Greg Lukianoff and Jonathan Haidt, is the culmination of this societal progression. In The Coddling of the American Mind, Lukianoff and Haidt define safetyism as being characteristic of three fallacies of thinking:

- Desiring a total avoidance of risk, harm, or verbal/social discomfort;

- Always trusting feelings first, such that emotional reasoning is more legitimate than logic or science; and

- Perceiving the world as a battle between good and evil, such that resulting tribalism allows for little to no good-faith discourse or compromise.

In that its adherents carry these mindsets into the courtroom, safetyism forms a helpful lens to categorize the changes we have witnessed in the jury pool. Each of these fallacies can be applied to the field of litigation when considering how jurors will view the evidence and arguments and arrive at their final decisions. And while the third fallacy lends itself to hasty party judgments and more combative, stubborn deliberations, this article focuses on how the first two fallacies inform jurors’ views of the evidence:

Risk Aversion

It appears that people’s tolerance for risk has plummeted, while expectations for safety have skyrocketed. Whether it involves a product, driving, a workplace, or premises, the authors’ prior research shows that many people now expect 100% safety 100% of the time. Jurors follow the same path—expecting little to no risk in their environment, products, or activities—and look to corporations and government agencies to keep them safe. Our initial data backed up these fears: for instance, a whopping 92% of respondents agreed that “companies should take every possible measure to ensure their products are 100% safe.”

Intuition Over Facts

“Hey, that’s not fair!” “Wow, that can’t be safe!” Everyone has probably made sudden exclamations like these. Are they based on reasoned, fact-based thought? Not often. People’s first reactions tend to be based on emotion, perhaps with a dash of past experience, followed by a process in which they rationalize how those feelings are correct (Murphy, Sheila, 2001. Feeling without thinking: Affective primacy and the nonconscious processing of emotion. Unraveling the complexities of social life: A festschrift in honor of Robert B. Zajonc, p.39-53).

Emotions help people more efficiently navigate the world and the people around them, but the justice system is based on evidence, law, and critical analysis. The “safetyist” problem occurs when jurors deem it acceptable to rely on their gut feelings to serve in place of logic and fact. Explicit jury instructions restricting emotion-based decisions only go so far. For the growing number of safetyists, “fairness” and “risk” are feelings that win the battle over reasoned thought. Factual truth makes way for “my truth,” which is really just feelings or intuition. Even if the defense has more scientifically sound evidence, safetyist jurors are thus able to discount it and favor their feelings of sympathy for the plaintiff, their corporate distrust, and their fear that they or someone they know may possibly be harmed.

New Research

The authors’ preliminary research both confirmed the prevalence of safetyism and uncovered a number of juror characteristics associated with such beliefs. Through questions about product safety, manufacturer responsibility, and more, respondents were classified along a “safetyism” scale. Those measuring high in safetyism tended to be liberal, have higher education, reside in urban areas, and favor the internet and social media as news sources.

Given the link between those characteristics and common plaintiff juror profiles, much could be hypothesized about the effects of safetyism on verdicts. But to flesh out our understanding of the safety-ist and test the direct relationship between safetyism and verdict outcome, a new online survey evaluated 220 additional jury-qualified respondents. This time around, participants were analyzed along multiple scales—not only by the initial safetyism scale, but more granularly by risk avoidance and reliance on intuition (the first two safety-ist thought fallacies). Questions identified respondents’ placement on these scales after collecting their reactions to a fictional lawsuit. The survey also assessed participants’ trust in various government agencies (e.g., EPA, FDA, OSHA) to keep people safe, as well as some personal and demographic factors.

The fictional scenario described the following case issues and claims about an herbicide product, “Canophyde,” produced by chemical manufacturer “Chemegent.”

- Canophyde is approved by the EPA (but banned in the EU) for use by approved applicators on commercial farms.

- The plaintiff has lived near commercial farms, where Canophyde had been applied, for the past 35 years.

- The plaintiff claims that scientific evidence shows Canophyde is carcinogenic and that he now has cancer as a result of exposure to the chemical through drifting spray.

- Chemegent denies that Canophyde caused the plaintiff’s cancer, arguing that years of studies prove it is not a carcinogen and that the product was properly labeled.

- Chemegent further argues that other herbicidal agents produced by other manufacturers have been found to cause cancer and that other nearby farms could have used those agents.

Participants responded with a verdict, as well as an indication of how strongly they desired to award damages and how angry they felt toward Chemegent. These responses were submitted to linear regression analyses to measure safetyism, intuitive thinking, risk aversion, attitudes toward government agencies, political leanings, and several demographics as potential predictors.

Verdict Predictors

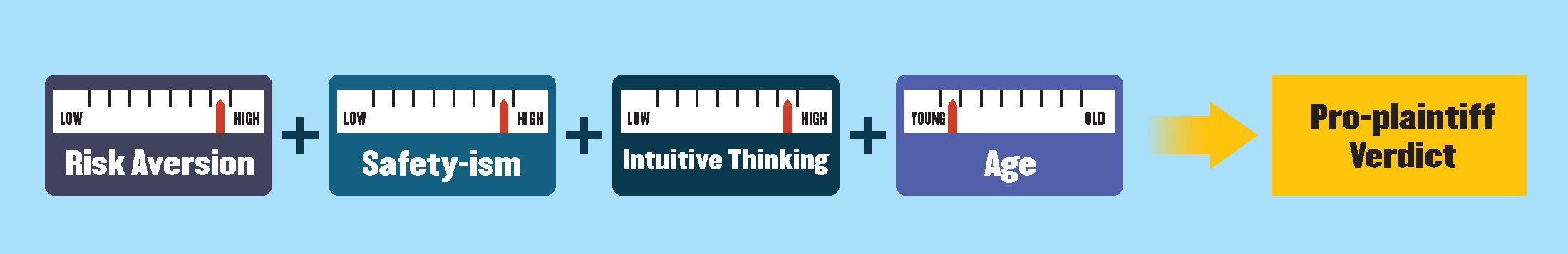

Ultimately, 45% of respondents voted for the plaintiff, 44% favored Chemegent, and 10% remained neutral. Results of the regression model revealed that higher safetyism, greater reliance on intuition, greater risk aversion, and younger age significantly predicted a pro-plaintiff verdict. Pro-defense jurors, in contrast, were low on safetyism, utilized greater fact-based thinking, accepted more risk, and were older than their pro-plaintiff counterparts.

Monetary Compensation Predictors

Among our respondents, 20% reported an extreme desire for Chemegent to compensate the plaintiff, 38% had a moderate desire, 22% slightly desired to compensate, and 21% reported no desire. Regression analysis revealed once again that higher safetyism, greater reliance on intuition, greater risk aversion, and younger age predicted greater desire to award the plaintiff damages. Low to no desire to compensate the plaintiff significantly related to low safetyism, more fact-based thinking, greater risk acceptance, and older ages.

Anger Toward Chemegent

Younger age and greater reliance on intuition were the strongest predictors of anger toward the defendant. The intuition finding is unsurprising, given that anger is an emotion and intuitive reasoning is rooted in emotions. However, in eliciting anger, respondents’ level of intuitive thinking could even outweigh their otherwise low safetyism. That is, participants with low safetyism and low intuition experienced little to no anger, as one might expect; but, low safetyism respondents with high intuitive thinking experienced anger toward Chemegent that was no different than high safetyism respondents. This finding suggests that low safetyism is good for defendants only to the extent that those jurors do not engage in intuitive reasoning; if they do, they are more likely to experience anger that can drive a high-damages verdict.

Desire to Punish Chemegent

Respondents were asked if they desired to award punitive damages to punish the defendant and deter similar behaviors. Among those who found for the plaintiff, 71% desired to award punitive damages. Interestingly, only greater risk aversion and younger age significantly predicted a stronger desire to punish Chemegent. Respondents who were older and more accepting of risk had little to no desire to punish the defendant.

Additional Findings

Additional significant findings offer insight into potential jurors’ decision-making:

- Plaintiff support significantly correlated to less trust in government agencies.

- Plaintiff support significantly correlated to greater liberalism on financial issues.

- Pro-plaintiff respondents believed jury damage awards for diseases such as cancer deserve more money than other types of cases.

- The greater the desire to award punitive damages against Chemegent, the less trust in government agencies.

- Safetyism significantly correlated to many political opinions:

- More positive views of Democratic Senators, President Biden, and Vice President Harris correlated to greater safetyism.

- More positive views of Republican Senators, former President Trump, or former Vice President Pence correlated to lower safetyism.

- Regarding verdicts, the only significant political rating was that more negative views of Donald Trump correlated with plaintiff support.

Strategies for the New Future

While there is no absolute answer to the safetyism dilemma, psychological science can point to strategies for alleviating some of its harmful effects. For example, in his book, The Righteous Mind, Jonathan Haidt portrays six elements of humans’ moral reasoning and explains how reaching out to decision-makers in as many of those ways as possible tends to gain more backing. The six reasoning markers are: compassion, anger, team cohesion, fear, avoidance of contaminants, and liberty. Plaintiffs have a certain advantage in selling their cases by appealing emotionally to more of these categories. Plaintiffs can generate compassion for injuries, anger over wrongs, pit sympathizers against reasoners, incite fear, and raise disgust over contaminants or injury. Defense teams therefore will need to supply counter-offensives on as many of these levels as possible, through as many avenues as possible—from voir dire to a strong thematic case story to motions with the courts.

Short-Term Strategies

Voir dire will be key to understanding jurors’ safetyism, risk aversion, and emotional decision-making habits. Many courts have restricted parties’ voir dire time, so asking for more voir dire time will be important, as well as cutting to the chase with questions. Pre-pandemic, there was often more leeway for building rapport with the jury panel, but extreme time crunches now often mean saying farewell to the basic pleasantries. The forefront should belong to questions that home in on safetyism beliefs, instinctual or emotional decision-making, and risk aversion. With so little time to waste, attorneys might consider conducting a voir dire practice session with mock jurors to practice sharpening questions and quickly forming cause challenges.

When it comes time to present the case at trial, themes will be more critical than ever in jurors’ understanding and acceptance of a defendant’s case. Jurors think in stories, so telling them a story with highlighted themes—repeated often and presented on slide headers—builds rapport, comprehension, and retention. To help defense jurors bridge the gap with stubborn plaintiff counterparts, remind jurors to hold each other accountable for the facts, evidence, and reason behind their decisions. Emotion has no place in their verdict decisions.

Some themes that could be helpful include:

- Facts Not Feelings

- Follow the Science

- Correlation Is Not Causation

- Probabilities Not Possibilities

- The Defendant Is Here for Justice, Too

Mid-Range Strategies

Corporate experts and company witnesses could benefit from a witness “school” that teaches them the company story, safety story, product development story, etc. The more witnesses are able to explain the history and reasoning of any product development, the harder it will be for plaintiffs to poke holes in the defense.

Motions for individual voir dire also can be very helpful because plaintiffs’ media strategies of advertising their biggest verdicts and fishing for new plaintiffs can influence jurors’ view of companies’ behaviors—explicitly and implicitly. Oftentimes, jurors may not be able to explain what media they have been exposed to or appreciate the impact of that exposure on their attitudes toward the defendant.

Lastly, file motions for single-plaintiff cases. As the number of plaintiffs increases, jurors begin to view the case as “Where there’s smoke, there’s fire.” (Leibold, J. “Does Trial Length Increase Jury Damages?” /insight/trial-length-jury-damages). What’s more, every plaintiff added to the case increases the cognitive demands for the jury, as they try to analyze that many more details. There are limits to what jurors can listen to, process, encode, and retrieve when it comes time to make a decision. When they are cognitively overwhelmed, they rely on “heuristics,” or mental shortcuts. In multi-plaintiff cases, the shortest route is to decide that all the claims must be valid since they all experienced the same illness or injury.

Long-Term Strategies

Ideally, companies identify key corporate witnesses before litigation ever occurs—witnesses who can be prepared to describe the company’s safety practices and policies, as well as the history of the safety development of any products or procedures. Well-prepared, high-level company representatives must be able to deftly counter the plaintiff’s claims of “profit over safety” with a “good company” story.

Multiple firms and defense teams need to be deployed for litigation across all 50 states. While there may be many working parts among the defense teams, it is critical for all involved to share strategies and themes that work. The plaintiff bar has a website to share experts, themes, and presentations. Defense firms would do well to establish their own collaborative website or working group, sharing witnesses, strategies, themes, stories, and voir dire tactics.

Conclusion

Defense counsel and corporations have a tough path ahead to combat jurors’ safetyism, risk aversion, lack of trust in government agencies, and emotional verdict decisions. Gen Z jurors are the most risk-averse generation yet (‘Generation sensible’ risk missing out on life experiences, therapists warn | Alcohol | The Guardian). However, culturally, all generations have embraced greater safetyism and risk aversion, just to different degrees. Thus, the safetyism problem is not going away soon. The sooner defense counsel and corporations can come together on strategies, the sooner they can fight back.

This article was originally published in the September 2023 issue of DRI's For the Defense. Republished with permission.