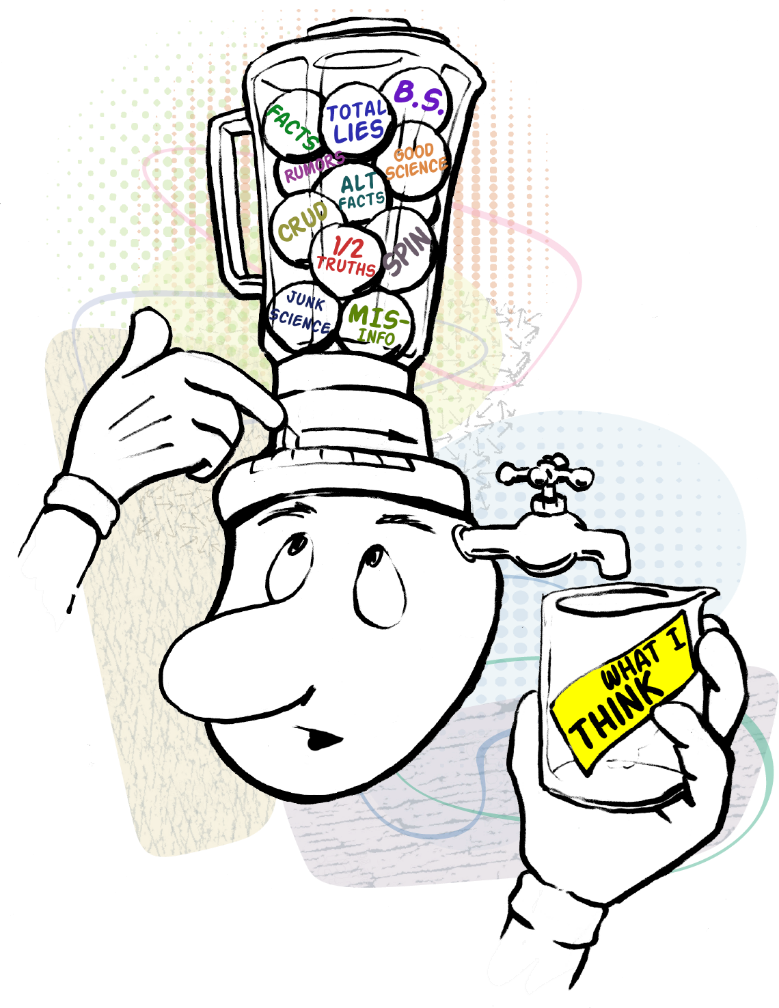

At one point, you could make a strong argument that misinformation about the novel coronavirus proliferated even beyond the virus itself. Unproven treatments, conspiracy theories, and the politicization of protective measures are but a few examples.

This probably should not surprise us. Misinformation is its own modern-day plague. Back in 2018, it was Dictionary.com’s “Word of the Year”—a reflection of its impact on our cultural climate. But when it comes to a deadly pandemic, about which it is so imperative we are all on the same page, the prevalence of misinformation hits that much harder.

There are many lessons to be learned from how the past two years played out. But for our own purposes in the legal field, it underscores more than ever the biases and misrepresentations that a defendant can be up against—and simultaneously, the importance of our best overarching counterstrategy: telling a complete, consistent, and credible story so jurors aren’t tempted to fill in the blanks themselves.

How Did COVID-19 Misinformation Happen?

Misinformation was always going to be a problem with COVID-19. As a May 2020 article in The Atlantic examined, the inherent draw of fresh content in our news feeds was amplified to its extreme by the burgeoning outbreak. In times of fear and uncertainty, we seek guidance—we want the most up-to-date information, the newest findings, maybe some semblance of hope. Unfortunately, proper science takes time. Reliable conclusions take time.

But what doesn’t take time, doesn’t respect nuance, and does attract views is the spouting of unqualified people with opinions and theories. In the words of the article’s author, “The feed abhors a vacuum.” We demand the latest, and algorithms largely unconcerned with a source’s credibility have been happy to oblige.

Granted, we could discuss at length the inconsistent and conflicting messages offered by government authorities, and the damage this response did to the public’s trust, as well as our ability to discern the severity of the circumstances and to select reliable information resources. But even health experts, struggling to stay abreast of developments and communicate them effectively, had their share of early missteps. Whether due to an abundance of caution, restrictions on media access, or simple mistakes, they provided rationed information riddled with qualifications, ambiguities, or generalities.

Some of that shortcoming was the inevitable result of the incremental, painstaking nature of science and medicine—yet some, too, was the result of underestimating the threat of misinformation and being ill-prepared to reach the public through modern means.

The rest is history. As the article argues, “Populist Twitter decries any misstep by authority as confirmation of wholesale ineptitude or corruption—as if a mistake anywhere casts doubt on expertise everywhere.” Those worth trusting began to lose many people’s trust. Meanwhile, social media platforms (and even some news outlets) did not share the same concerns as medical experts for speaking with truth and precision.

In the absence of quality information, misinformation filled every crack and crevice.

How Do Jurors Respond to Gaps in Our Case Stories?

You might imagine how the spread of COVID-19 misinformation relates to our goals as storytellers in the courtroom. As those who are similarly tasked with convincing an audience of the importance and accuracy of our narrative, we cannot afford to make the same mistakes or incur the same doubt.

Humans think in stories, meaning an incomplete narrative is unsatisfying, even frustrating. This is why mystery novels are such page-turners, and why crimes with no apparent motive are so confounding. Therefore, if you leave gaps in your defense case, jurors will fill them in—and you might not like how.

Whether it comes from their own heads or from a vocal juror in deliberations, jurors will piece together what they’ve heard with connective tissue built from their own attitudes and experiences, or worse, the plaintiff’s case. Given prominent anti-corporate bias among jurors and increased media coverage of corporate wrongdoings and high-damage verdicts, there’s a lot for them to draw from that could hurt your desired outcome.

But while we cannot ever stop jurors completely from introducing their biases and assumptions into the mix, we can limit the instances where they feel compelled to reference them.

What We Can Do to Improve Our Case Stories

The advantage we have over the pandemic-immersed medical community is that we have time to craft and assess and polish our cases with all available information; our cases are not reliant on “breaking news.” We therefore have opportunities throughout the litigation lifecycle to help put the right story in front of the right audience:

1) Learn What Story Needs to Be Told

Evaluating your case through early case assessment or an inductive focus group gets the ball rolling on developing a narrative structure based on strong, memorable case themes. Getting feedback from mock jurors representative of your venue prepares you for the perspectives they have and the words they use to describe and rationalize your case.

Equally important, you’ll learn what questions jurors have—that is, you will identify gaps and blind spots in your case and areas where additional witness testimony might be helpful.

2) Craft a Complete Story, Filling Gaps Wherever Possible

With the bones of your thematic story in place, your next goal will be to insert evidence and testimony around their corresponding themes and fill in remaining gaps. A few common, defense-case blind spots that invite misinformation are:

- A failure to provide believable motives and context for company actions/inactions

On a large scale, filling this gap involves crafting an affirmative case story, rather than simply contesting the plaintiff’s claims. A “good company” story—who you are, what you do, how you go “above and beyond,” etc.—humanizes your client and prevents jurors from seeing the company as a negative caricature about whom they can assume the worst.

On a point-by-point basis, e.g., if the plaintiff presents your employee’s poorly worded email to claim your client favored profits over consumer safety, you must also try to give a persuasive rationale about the many factors that go into company decisions.

- In personal injury cases, a failure to provide alternative causation arguments

It is tough for jurors who are sad or angry about a plaintiff’s injuries to exit deliberations without casting blame somewhere. If the defense can help complete the story by offering alternative causation arguments, jurors are less likely to jump to the conclusion that the cause was your client.

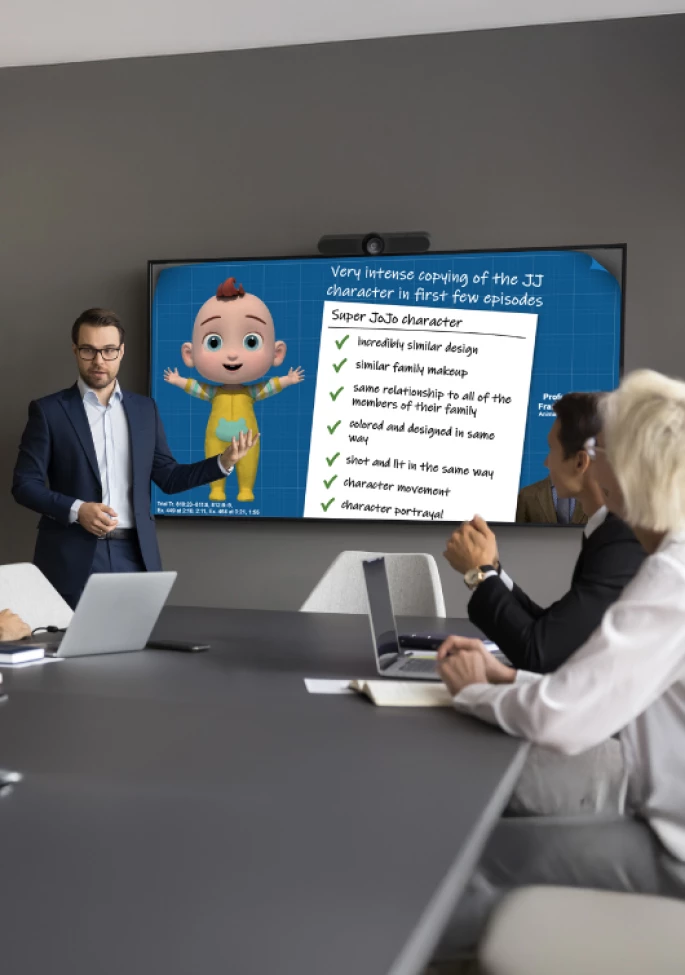

- A lackluster visual presentation (especially for complex cases)

Well-made graphics will help jurors digest the concepts you present and interpret them how you intend. Moreover, modern jurors expect a strong graphical element; they’ll be more receptive to presentations that more closely exemplify the visuals they see day-to-day.

To aid in your efforts at this stage, we recommend performing deductive jury research to test the themes and witnesses you have in place in a more formal setting. Further, communication training can bolster the influence of your key witnesses, especially your chosen corporate representative and your experts, as they help tell your story.

Jurors look to experience and authority as a measure of credibility (and we’ve seen what happens when they can’t find it).

3) Fight the “Reptile”

Simply put, the plaintiffs’ “Reptile Strategy” revolves around conjuring fear and anger among jurors about the defendant’s apparent misconduct—convincing them the defendant poses a danger to the community at large and arguing that the jurors alone have the power to protect the community and ward off future threats.

As the pandemic has taught us, emotions like these stir an even greater need for answers, and jurors will get them from somewhere. Thus, defendants must take additional measures to combat the Reptile (or even reverse it against the plaintiff) and help jurors focus on facts and logic when deciding the case.

4) Adjust the Audience So Your Story Is Heard Fairly

Media platforms may be reticent to do so, but at least we have the opportunity to identify and remove the most extreme voices from the venire. Striking those jurors with the most damaging biases goes a long way toward limiting the spread of harmful viewpoints in the deliberation room.

If you’ve performed jury research along the way, you may have access to a “juror distinguishers” profile: a list of factors shown to have a statistically significant influence on jurors’ case-relevant leanings and opinions. Either way, assistance with voir dire development and jury selection from an experienced consultant increases your ability to track problematic jurors and make informed strikes and cause challenges.

Final Thoughts

The misinformation we’ve seen permeate the public discourse surrounding COVID-19 is as frustrating as it is dangerous. It is also, in part, a natural outcome of our search for answers concerning our own safety and that of our family and friends.

As courtroom storytellers, the best we can do is learn lessons about how not to invite the spread of misinformation and false narratives among those who decide our cases. We must discover where the cracks are and fill them with convincing evidence and argument.

Ironically, the pandemic that has provided us these crucial reminders is the very same pandemic that makes certain jury research services more complicated to perform. However, nearly all of the services discussed above can be performed remotely with little change in how they’re carried out. And while substantial research (like a mock trial or focus group) comes with certain caveats and limitations when performed online, it remains a valuable resource to establish and hone an effective narrative.

We encourage you to contact our team to discuss which of these services may be right for your case.

Illustration courtesy of IMS Senior Graphic Designer John Ilg.

View this article on The National Law Review here: How We Can Learn From Misinformation in the Courtroom (natlawreview.com)

View the updated version of this article here. It can also be found on Law360.com.