This post offers excerpts1 from an interview with IMS Jury Consulting & Strategy Advisor Dr. Christina Marinakis on professional poker player Zachary Elwood’s podcast: “People Who Read People.” Listen to the full episode on YouTube, iTunes, Spotify, or iHeartRadio.

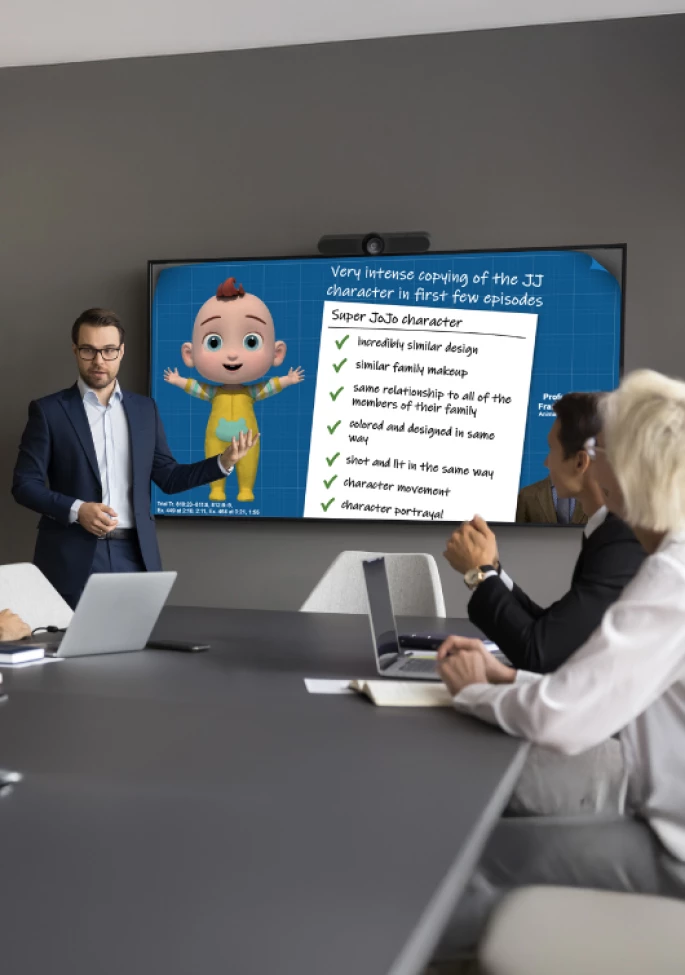

On the Game Theory of Voir Dire

The best jury consultants and attorneys who participate in voir dire are able to anticipate the next side’s move and what the consequences of that move will be. So, when I’m trying to decide who we want on the panel, the only way we can do that is through the striking process. I have to think about, “If we strike this juror, who’s going to take their place?”

For example, if there’s 12 jurors on the panel, [and] we strike juror number 4, now juror number 13 is going to move into that seat. Now the panel composition has changed—and then I have to think about, “Who is the other side going to strike?” If the other side strikes juror number 9, now juror number 14 is going to move into that seat.

And you have to be able to anticipate: Who is the other side going to strike, and who is going to move into those seats? And how many strikes do each of you have left? If you use your strikes on a juror you might not want, but not the worst juror, well if someone worse takes their seat, and you run out of strikes, you end up with an undesirable jury.

It absolutely is a game of chess—and because it moves so quickly, it’s really a game of speed chess.

On Jurors’ Voir Dire Responses and Body Language

Whether a juror is a good juror or a bad juror—or even if it’s just the difference between a bad juror and a very bad juror—sometimes depends on not what they say, but how they say it.

So, for example, there may be many people in the audience who have had a negative experience with something. Let’s pretend: It’s an employment case, and [assume an attorney is] representing the company who is being sued because they discharged someone, and it’s alleged to be a wrongful termination. So, there might be multiple jurors there who’ve been fired from a job, but how they respond to that situation will determine who we get rid of on the panel.

The attorney might say, “How was that experience, when you lost your job?” If one person says, “You know, that was a tough experience,” and another person says, “I was devastated,” there’s a difference!

If our side only has one strike left, I’m going to strike the person who says they were devastated, and they say it with a sigh, and you can see the pain in their face. As opposed to someone who says, “Yeah it was tough”; they say it quickly, they don’t seem upset, they were able to move on—versus someone who might still be clinging on to the pain of that experience.

So, I’m looking at their facial expressions. Do they look pained, do they have a furrowed brow, are they hesitant, is there a quiver in their voice? Do they look sullen and sulky? Or are they confident and able to move past it?

On Using Your Own Body Language and Question Phrasing to Get Jurors to Open Up

Almost subconsciously, if we see someone doing something, we want to emulate it. If you’re raising your hand when you are just asking the question, “How many people feel this way?”, that almost subliminally sends the message to the jury, “It’s okay, raise your hand.”

And it also goes to the way that you ask the question: If you say, “Does anyone feel that way?”, it almost implies that this is an unpopular belief or an unacceptable belief, versus when you say, “How many of you…,” which implies that this is a common belief, and certainly there’s going to be people in the audience who feel this way.

Using that body language and the wording of the question, together, gets people more likely to raise their hand to those types of questions.

Another example is just nodding your head slightly [when the juror is speaking]. Just very slowly nodding [to suggest], “Yes, I’m following you, I’m feeling you.” Match the juror’s facial expressions. If the juror is wincing, the attorney should be wincing. If the juror is smiling, the attorney should be smiling.

These are all techniques that I’ve learned in my experience as a clinical psychologist just doing therapy. It’s about matching a person’s emotions and reflecting back to the juror what they said.

On “Mini-Openings”

In most jurisdictions, the lawyers are allowed to give a little synopsis of the case before they start questioning jurors, to help orient the jurors to each side’s main arguments.

I had noticed that when my clients were giving very strong mini-openings and coming right out of the box and saying, “You know what, our product was approved by the FDA, the plaintiff who is alleging it caused her cancer has a family history [of cancer], and we firmly believe that our client did not cause her cancer”—now all of a sudden, you started getting jurors raising their hands who are saying, “Well, wait a minute, if your product is approved by the FDA, then I’m already on your side,” or “If she’s got a family history of cancer, then no way your product caused her cancer! I can’t be fair.” And now we’ve just lost our best jurors in the case.

So, I then recommended to a client who trusted me, “You know what, I think you need to throw your mini-opening. Give the bad parts of your case.” We did that, and the other side came out really strong, and what happened was the jury started saying, “Well, obviously I’m going to side with the plaintiffs. Your CEO already admitted wrongdoing, and clearly a lot of people have died from your product or gotten cancer. I can’t be fair [to the defendant].” We got rid of 27 jurors in that case for cause.

Who are the people that are left? The people that are left on the panel are the people who heard all of those terrible things about my client and about the company, who nevertheless still kept an open mind and were still willing to be fair. Those are the jurors who are truly going to be fair and impartial—and now the other side, they didn’t identify any people who might be inclined to side with the defense.

It really is counterintuitive, but I tell my clients, “Look, voir dire is the time to identify those people. Do you want those people to say those horrible things about you now, in voir dire, or would you rather have them say that in the deliberation room when they’re trying to come back with a verdict?” And then you know what? You’ve got your jury seated, now come out with a really strong opening statement.

For more behind-the-scenes tips and tales, check out the full interview and learn even more about the crucial role of strategy and psychology in jury selection. (Illustration courtesy of IMS Senior Graphic Designer John Ilg.)

1 For ease of reading, these quotations were edited for brevity and clarity.