We have written a fair amount about the importance of getting jurors to reveal bias in voir dire and subsequently admit they cannot be fair, with the goal of maximizing cause challenges and removing your riskiest jurors from the panel. But equally important is saving the jurors who are likely to support your case. When it comes to voir dire, there are three skills necessary for reducing the likelihood of having your best jurors kicked for cause: hiding your keeps, rehabilitating jurors, and defending a cause challenge.

Hiding Your Keeps

The first stage of preserving your good jurors is not to identify them in the first place.

Though perhaps counterintuitive, avoid divulging your good facts during voir dire or in a mini opening because you run the risk of jurors speaking up in agreement with your position. Sure, you may feel more confident in your case as a result, but these jurors are likely to become prime targets for opposing counsel to challenge—and they are of little use to you if they get stricken. In the event your best jurors speak up regardless, there are other strategies available for making the most of the situation before attempting to rehabilitate them.

In a similar vein, use your time to ask questions that seek to identify only those who are likely to agree with the opposition. In most instances, your questions should be one-sided. For example, rather than asking jurors whether they think there should be more or less government regulation of corporations, defense counsel would only want to know about those who think regulations should be stricter. In a written questionnaire, the ideal question would be:

Do you think there should be more government regulation of large corporations?

□ Yes, much more □ Yes, somewhat more □ No

In an oral format, defense counsel would want to ask, “How many of you think the government should do much more to regulate large corporations?” In both of these instances, notice that the goal is to identify the people at the furthest end of the spectrum—that is, not just those who think there should be more regulation, but those who feel there should be much more. We call this “identifying your strike-able minority.”

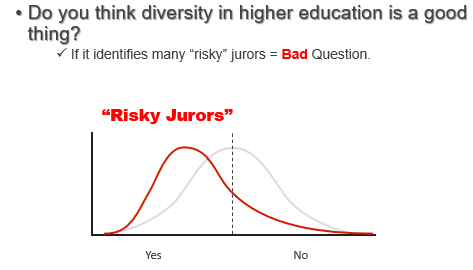

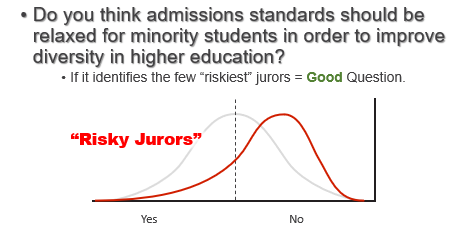

This is because it is not enough to simply ask questions that identify traits of your risky jurors; you need to consider the likely distribution of responses. For instance, if more than 50% of the panel is likely to raise their hand in response to your question, the information is less useful to you; you will not have enough peremptories to strike them all, and you probably will not even have the time to follow up with each of them to try for a cause challenge. Rather, your question should seek to identify the worst of the bad—the top 10 or 20%. A question that only a handful of jurors respond to will help you identify your riskiest jurors and know where you will need to focus your efforts or use your precious strikes.

On the flip side, if the vast majority of the panel raises their hands in response to your question, you have actually done your client a disservice, because you have now identified the few jurors who did not raise their hands as being priority targets for your opposition. If that happens unexpectedly, your best course of action would be to move on quickly so as not to draw attention to the few jurors who dissented, but attempting to avoid these questions in the first place is all part of the strategy to “hide your keeps.”

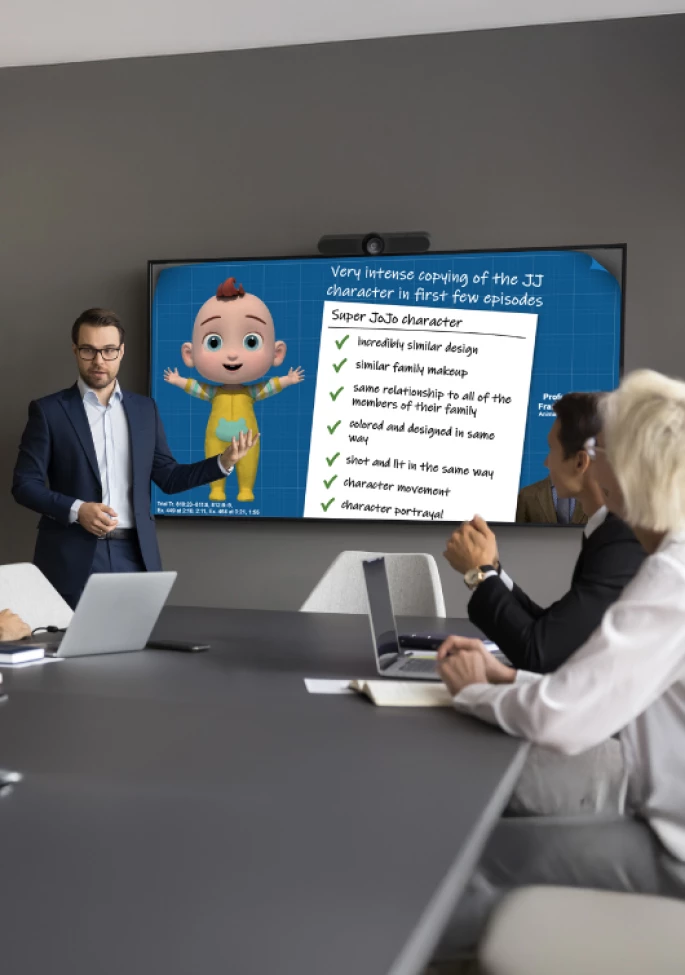

Figures 1 and 2 provide an illustration of this concept in the context of a discrimination claim. The question in Figure 1 has the unintended consequence of exposing the very best jurors for the defense.

Figure 1

Figure 2

Rehabilitating Jurors

Although it is important not to do opposing counsel’s work for them by identifying your keeps, a skilled adversary will undoubtedly elicit responses from the jurors likely to respond favorably to your case. Here is where the second stage of preservation comes into play. Rehabilitation is the skill of talking your good jurors off the ledge after they have said something that could be potential grounds for a cause challenge.

By nature of having the last word in voir dire in most jurisdictions, defendants generally have the upper hand when it comes to rehabilitating jurors (although plaintiffs should certainly attempt to “pre-habilitate” their good jurors before the defense has a chance to pose questions). For defendants, it should be obvious by the end of the plaintiff’s voir dire which favorable jurors you are at risk of losing for cause, so be sure to reserve some time to target these individuals for rehabilitation. This is best done near the end of voir dire, after you have already encouraged your risky jurors to admit they cannot be fair—else you pose a line of questioning that inadvertently rehabilitates those risky jurors, too.

Questions typically effective at rehabilitating jurors include asking whether they can listen to the evidence, set aside any experience or opinions, be fair to both sides, and follow the law that the judge provides. For example, if you were the defense lawyer in a malpractice case, you could rehabilitate a likely defense juror by asking the following:

Q: So, your father was a doctor?

Q: But you would acknowledge that all doctors are not the same, true?

Q: And some doctors make mistakes or exercise poor judgment from time to time, would you agree?

Q: And you don’t know any of the doctors involved in this case, correct?

Q: Will you judge the witnesses who testify in this case by what they say here in the courtroom, rather than based on some opinion you have of doctors in general?

Q: Can you set aside whatever general feelings you may have about doctors or malpractice lawsuits and judge this case on its merits?

Q: If the plaintiffs prove their case against the defendant, could you find in their favor?

Q: The court will give you certain instructions as to what laws you should apply. Will you be able to follow those laws despite any general opinions you may have?

Q: So, will you be able to give a fair shot to all parties involved? Thank you.

Despite all your best efforts, sometimes the most assurance jurors will provide is an assertion that they will “try” to be fair or “try” to set aside their biases. For some judges, this is enough to deny the cause challenge, but for many judges, and by statutory or case law in some jurisdictions, this equivocation is insufficient to establish that the juror can be impartial. In these instances, you will need to spend a little extra time getting the juror to make the commitment. We frequently recommend the following:

“So if you were a pilot, and we were about to take off and I asked if you’d be able to land the plane safely: If you said you’d “try your best,” then you would understand that we wouldn’t feel too comfortable getting on that plane, right? It’s a similar kind of thing here. So, we need a little more reassurance from you than just trying. We need to know, can you listen to the evidence, apply the law that the judge gives you, and be fair and impartial to both sides?”

Defending a Cause Challenge

Defending a cause challenge involves similar steps to making a cause challenge. That is, defending counsel should cite the prospective juror’s relevant verbatim responses from questionnaires and oral voir dire, cite the applicable statute for cause challenges, and this time explain why it does not apply, including – most importantly – explaining why rehabilitation efforts were successful.

In most jurisdictions, there will be supporting case law giving judges wide latitude to reject cause challenges for jurors who have revealed potential bias but subsequently committed to following the law. Many judges are already inclined to deny a cause challenge due to fears of running out of jurors or not completing jury selection within the timeframe promised to the venire members. So, when you are armed with case law and sound reasoning for why the judge should deny the challenge, you are in a stronger position to prevail on the argument, forcing opposing counsel to use a peremptory challenge or risk having the challenged juror seated on the jury.

Final Thoughts

For many clients, we are facing an uphill battle when it comes to jury selection. Large corporations rarely have the upper hand when it comes to defending cases against injured or deceased plaintiffs. This makes it even more imperative that we save the few defense-minded jurors from opposing counsel’s attempts to rid them from the panel. The techniques described above are tools that every defense counsel should be prepared to use in voir dire.

For additional assistance with getting the best jury possible to hear your case, partner with our experienced team on your next jury selection.