Whether it’s as small as convincing a six-year-old to go to bed at 8:00 pm (and stay in bed), or as big as nailing down the terms of a professional contract, we’re negotiating constantly.

But are we negotiating optimally? After all, there’s more to it than just two sides reaching an agreement. When you break a negotiation down, there are three key areas—planning and strategy, psychological factors, and communication factors—which contribute to the direction and success of a negotiation.1

To help you increase the likelihood of achieving better outcomes in your future negotiations, this three-part series will examine each of those key areas one by one, starting with planning and strategy.

Negotiation Planning and Strategy

Consider, for example, a dispute over a trucking accident:

A semi rear-ends a car, and the driver of the car claims to have a significant back injury and soft-tissue damage, saying he will never work again. Such a case has the potential for very high damages. The trucking company knows there is liability, but the plaintiff’s demand is extreme. So as the defense, how should you approach negotiating a settlement?

There are multiple moving parts that should be taken into consideration: What insurance policy limits are in place? Is the plaintiff malingering or are the injury claims valid? And if the injuries are legitimate, what amount of money is a fair offer?

The answers to these questions (among others) can help inform the three major components of your negotiation strategy:

- What is your reservation price or walk-away value? At what dollar amount is it more beneficial for you to go to trial?

- What is your realistic end goal? What dollar amount, or range of dollar amounts, would you be happy with?

- What is your initial offer? What concessions will that offer allow for?

1. What Is Your Reservation Price/Walk-Away Value?

When is going to trial the better decision? At what dollar amount does it seem more beneficial? This is the “walk-away value”—the point where the cost of an agreement is greater than the cost of not reaching an agreement.

Considerations include the likelihood of winning a trial, the amount of money a jury could award if they find in favor of the plaintiff, and the potential of setting precedent with damages for similar future cases.

It is particularly difficult to have an unbiased view on these likelihoods and dollar amounts. When attorneys have put a lot of work into a case, it can be difficult to see the forest for the trees, and jurors may see things from a different perspective. Mock trials can be very helpful to assess accurately the risks of going to trial and the range of potential jury awards.

2. What Is Your End Goal?

Once the largest acceptable agreement has been determined, focus on where you actually want to end up. What is a realistic end goal that you and your client would be happy with? Obviously, the party making the demand will want more money and the defense will want to pay less money; but realistically, given the facts of the case and the demand from the counterparty, what amount would be agreeable?

When coming up with this number, you should consider (1) policy limits, (2) what happened to the plaintiff, (3) the extent to which the defense is responsible for what happened, and (4) what a fair number would be considering what happened.

3. What Will Be Your Initial Offer?

Once your walk-away value and end goal have been determined, start to plan backwards, and consider what your opening offer should be. Critically, the first number the defense offers will impact any future counteroffers from opposing counsel, as it will serve as the reference point; furthermore, it will affect your ability to offer meaningful concessions.

Here are some tips for determining your initial offer:

- Concessions should suggest a show of good faith.

Starting with a lower offer leaves room for later concessions. But how much lower, and how big should the concessions be?

Well, concessions should show good faith. Using a simple example, if your end goal is $300,000, starting with an offer of $295,000 and making concessions in $1,000 increments likely will not accomplish your goal. But starting your initial offer low enough so that concessions can be adequately large will actually help send the message that you’re doing your best to reach an agreement. In this example, starting at $240,000 would more likely allow the defense to make a few $20,000 concessions—indicating that you are serious about reaching an agreement.

Granted, some people don’t like playing this game and would rather make a reasonable offer and stick to it, making no concessions. This is a negotiation tactic known as the “Boulware Strategy.” While there is some evidence this can be effective in the right situation, more often it can aggravate the counterparty because they are the only one making concessions. Therefore, starting with an offer that is below your end goal and offering concessions tends to be preferable.

- Estimate the counterparty’s walk-away value.

Offering a value just over the opposition’s walk-away value—the point at which they would rather go to trial than reach an agreement—is the most favorable agreement you can make. Obviously, this dollar amount is typically unknown.

To the extent possible, try to determine the lowest amount your opponent might be willing to accept. That way, if your client is happy to settle at, say, $300,000, but it turns out the counterparty’s walk-away value is $290,000, you can save your client $10,000 by not jumping to your end goal right away. In other words, starting lower and making concessions up to your opponent’s walk-away value can help save money.

- Low-ball offers can cut off communication.

On the flip side, an initial defense offer that is too low can send a signal that you are not reasonably trying to reach an agreement, thereby damaging communications.

So, if the defense’s end goal is $300,000, an initial offer from the defense of $50,000 may backfire—you may have been planning to make large concessions, but there won’t be any concessions to make if the counterparty cuts off communication. Even if they continue talks, the rest of negotiations might be soured.

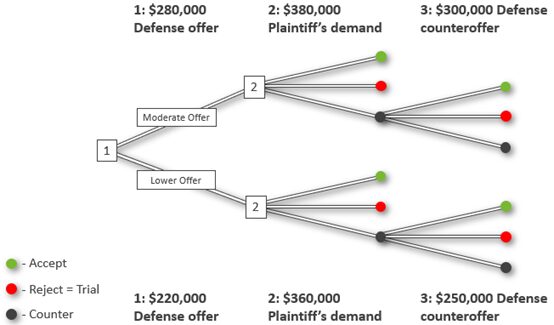

Therefore, the defense’s initial offer is a balancing act. Take the example graphic below, which lays out some options and their potential outcomes:

In this example, after ruling out offers that were too low, we landed on either a moderate offer of $280,000 or a lower offer of $220,000—both in the hope of reaching our end goal of around $300,000. As you can see, with the lower offer we have a greater potential for a few favorable results:

- The counterparty will likely make a smaller counterdemand (an effect we will discuss further in Part 2).

- You’ll have more room to negotiate, and your next offer can still be under your end goal.

- Your concessions can be larger (e.g., $30,000 instead of $20,000) as a stronger show of good faith.

Final Thoughts

Because many factors can affect the success of a negotiation, it is important for counsel to work out the various scenarios in advance and plan accordingly.

Walking into a negotiation with your goals, initial offer, and opponent’s potential responses in mind will help you make subsequent decisions and communicate the proper messages to move you toward your ideal outcome.

Part 2 of this series goes on to discuss the three psychological tools you can use to improve your negotiation outcomes.

View this article on The National Law Review here: Negotiation Planning and Strategy Tools (natlawreview.com)

References

1 Note: Sometimes counsel is provided with patently unrealistic goals or walk-away values. For instance, in one recent trade secret case, the plaintiff was asking for $19 million, while the defense’s settle authority was 0.1% of that number. In such situations, there is no real foundation for a successful negotiation; naturally, this series is instead geared toward situations where there is a reasonable likelihood for resolution.